|

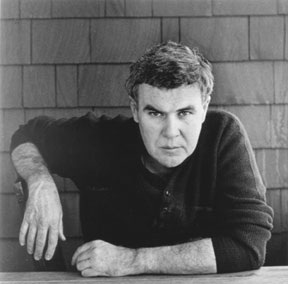

Raymond Carver, one of America’s greatest short story writers, is equivalent in fame to that of Ernest Hemingway. Even though Carver hated the term “fame” and deemed it worthless — and that it complicates a writer’s expectations about “where they are going” — he never let his rising popularity diminish the sincerity of, or complicate, the small-town characters whom communicate his ideas. Born in Oregon in 1938, Carver was raised in a town called Yakima, Washington where he hunted waterfowl and fished for trout as a child. His father, Raymond Carver Sr., held various jobs through Washington and California, working as a sawmill operator, and helped work on the Hoover Dam and “never got recognition for it,” Carver says in his essay “My Father.” He cites his father’s repeated use of what his mother called “nerve medicine” as a source of his own alcoholism. His dad was also a prime inspiration for Carver’s interest in storytelling: My dad would tell me stories, anecdotes really, no moral to them, about tramping around in the woods, or else riding the rails and having to look out for railroad bulls. I loved his company and loved to listen to him tell me these stories […] I realized that he had this private side to him, something I didn't understand or know anything about, but something that found expression through this occasional reading. I was interested in that side of him and interested in the act itself. Carver decided he wanted to become a writer when he spotted an ad in Writer’s Digest for a writing course run by the Palmer Institute (which still exists, by the way), but got “bored” with the work after a few assignments. After he met his first wife, Maryann Burk Carver, in 1955, he was too overworked by his job and finishing his B.A. degree at Humboldt State College to write freely, but managed to get published in the Western Humanities Review. He stuck to short stories and poems because he could finish one in one sitting, which he struggled to find time for amid the penury, effects of bankruptcy, child bearing, and working “crap jobs” as a janitor, as a librarian, or even at the sawmill, like his father. This is when Carver’s drinking habit became prevalent. He says, I began to drink heavily after I'd realized that the things I'd wanted most in life for myself and my writing, and my wife and children, were simply not going to happen. It's strange. You never start out in life with the intention of becoming a bankrupt or an alcoholic or a cheat and a thief. Or a liar. But Carver never really wrote directly about his alcoholism. However, most of the iconic characters in his short stories are struggling with a personal sense of dissatisfaction with life, a side of Carver’s personality that may have made him turn to the drink. It’s the way Carver wrote about this blue-collar lack of luster that made him such a figure in the realist movement of the 60s and 70s. And so did his drinking. After blacking out in police stations, appearing in courtrooms, and almost tainting book deals, Carver eventually beat his attachment to his “nerve medicine” in May of 1977 after he was offered a contract to write a novel by Fred Hills, head of McGraw-Hill Publishing. With the help of AA, Carver reached sobriety, the feat he was most proud of in his life. Although he states that his alcoholism and the subsequent recovery was never injected directly into his fiction, the stories he admires most have undeniable connection to the “real world,” those that have grounding in human experience. None of my stories really happened, of course. But there's always something, some element, something said to me or that I witnessed, that may be the starting place […] The fiction I'm most interested in, whether it's Tolstoy's fiction, Chekhov, Barry Hannah, Richard Ford, Hemingway, Isaac Babel, Ann Beattie, or Anne Tyler, strikes me as autobiographical to some extent. At the very least it's referential. Stories long or short don't just come out of thin air. And Carver says that it is this “reference” to our own lives is pervasive in the great writers of fiction, from Hemingway in his short stories, to Kerouac in On the Road, even to some writers of biography and memoir (I once heard an argument from a friend who said Elie Wiesel’s Night was fictional to some extent). What he calls 'autobiographical fiction" is inescapable for the writers who write with direct connection to world around them. About this ‘writing from experience,’ Carver says Everything we write is, in some way, autobiographical […] Of course, you have to know what you're doing when you turn your life's stories into fiction. You have to be immensely daring, very skilled and imaginative and willing to tell everything on yourself. You're told time and again when you're young to write about what you know, and what do you know better than your own secrets? But unless you're a special kind of writer, and a very talented one, it's dangerous to try and write volume after volume on The Story of My Life. A great danger, or at least a great temptation, for many writers is to become too autobiographical in their approach to their fiction. A little autobiography and a lot of imagination are best. The above quotations were taken from The Paris Review's, Art of Fiction, no 76.

1 Comment

|